In his invaluable book, In Search of the Miraculous, Peter Ouspensky quotes these words from George Gurdjieff:

Fusion, inner unity, is obtained by means of ‘friction,’ by the struggle between ‘yes’ and ‘no’ in man. If a man lives without inner struggle, if everything happens in him without opposition, if he goes wherever he is drawn or wherever the wind blows, he will remain such as he is. But if a struggle begins in him, and particularly if there is a definite line in this struggle, then, gradually, permanent traits begin to form themselves, and he begins to ‘crystallize.’

These are passionate words and, to understand them, we have to begin with our own experiences of presence, our own remembrance of moments of higher consciousness. No one can infuse verification in another. Consciousness is truly beyond words as the Sun is beyond shadows. But your personal verification is your Sun.

As our verification of the miraculous nature of presence—of higher states of consciousness—deepens, our desire to evoke presence deepens, and the inner struggle begins again on an ever higher level. Of course, there are different points of view about the nature of this struggle. Some teachers remind us that the struggle itself is an illusion, that Divine Presence isYou, and therefore there is nothing to be done. Indeed, they would say that we must drop the struggle entirely. Nevertheless, however it is characterized, the true spiritual path will always refer to the same epic journey from here to here, and we are thrust back on our individual experience of this journey.

From my own understanding, I can only say that the achievement of a higher state must be won. Every effort to become present to this moment is necessarily met by a powerful force within that strives to undermine that effort. This is what Gurdjieff meant by the “struggle between yes and no”—the Struggle of the Magicians.

This effort to be aware of ourselves, to engage presence, can take many forms. In Orthodox Christianity – as expressed in the Philokalia — this effort is embodied in the Prayer of the Heart; in Islam, by recitation of the Koran; in Zen, by formal meditation; in Sufism, by the Zikr; and in the Fourth Way, by self-remembering.

Simply put, self-remembering is awareness intentionally brought to the Higher Self, whose existence can only be found in this very instant. From one point of view, presence is the Higher Self; from another point of view, presence is the awareness of the Higher Self.

Presence is deepened by the very effort to be present, and the source of this effort comes from our most intimate desire to escape the bondage of time and death. As our experience of presence increases, our sensitivity to the loss of presence also increases. The comparatively lifeless inner state that follows in the wake of presencebegins to catapult us into another effort to remember ourselves. This practice—self-remembering—is the hub of the Fourth Way system.

One way to evoke self-remembering is to practice divided attention. This method is deceptively simple yet quite difficult to prolong. You place your attention upon yourself while simultaneously placing attention upon an object within your environment, whether internal or external. Your attention literally becomes a double-headed arrow ↔. It is actually divided.

When you divide attention, you will experience a change of consciousness, even if it is quite subtle. Please try it for a few seconds to see if this is not true. Direct the attention toward yourself and simultaneously toward the words you see on your computer screen. Please try to maintain this divided attention. Now listen to the silence touching your ears. Now try to feel yourself sitting in the chair.

Clarity increases. Awareness increases. The level of your consciousness rises.

The effort to be aware of ourselves (to raise our level of consciousness) is distinct from any resulting higher state of consciousness, and yet they are intimately connected. This can be likened to physical exercise. We walk quickly up five flights of stairs. This is the effort: the heart beats more rapidly; the blood circulates faster. A sense of well-being results: this is the state. The effort to divide attention is the means but not the end. The final aim is raise the state of consciousness and then to prolong that state.

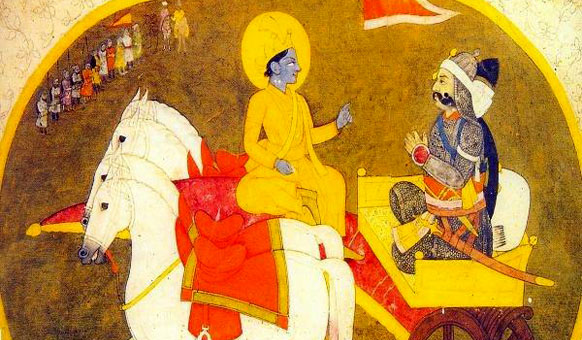

All great spiritual traditions are based on the internal quest to unveil presence in this immediate instant. The voyage of Odysseus to Ithaca mirrors our own voyage home to the present moment. The transfiguration of Christ is the transformation of sleep into presence. The story of the Buddha is the story of awakening to one’s own Higher Self in the moment. The ascension of Mohammed is the redemption of presence.

The voyage to the present moment is truly a hero’s voyage, and the opposition to it is equally dramatic. In an upcoming article, we will speak about the nature of this opposition both in its most subtle form—a single thought, and in its mythical depictions—the monsters and demons of the great traditions and myths.

But in the meantime, try to make the effort to remember yourself and try to observe the nature of the force that carries you away from this sacred effort. In the Work, this force is called imagination, the substance of sleep.

Thomas Fenn